The Legislative Process

Overview

The Legislative Process

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Analyze the Texas legislative process (aka How a Bill Becomes a Law)

Introduction

This section discusses the Texas legislative process.

How do Legislators Make Decisions?

The people we elect to be lawmakers determines the rules we have to live by. So, it is good for us to understand what influences the decisions of lawmakers. Unfortunately, we can't know for sure. We would like to believe that whatever they promised on the campaign trail will be what they deliver on in office. That is often not the case. We know that public opinion polls sometimes reflect how lawmakers will decide to vote on issues. We also know that interest groups play a role in how decisions are made. One of the biggest factors is probably political ideology. Is the politician a conservative or a liberal? Or, partisanship might be a factor. Is the politician a Republican or a Democrat? At the end of the day, it is for us to determine whether we believe that politicians are doing the right thing regardless of the influences on their decisions.

Setting the Stage and Making the Rules

The legislature meets every odd-numbered year to write new laws and to find solutions to the problems facing the state. This meeting time, which begins on the second Tuesday in January and lasts 140 days, is called the regular session. The governor can direct the legislature to meet at other times also. These meetings, called special sessions, can last no more than 30 days and deal only with issues chosen by the governor.

On the first day of each regular session, the 150 members of the House of Representatives choose one of their members to be the Speaker of the House. The speaker is the presiding officer of the House. The Speaker maintains order, recognizes members to speak during debate, and rules on procedural matters.

The Speaker also appoints the chairs and vice chairs of the committees that study legislation and decides which other representatives will serve on those committees, subject to seniority rules. There are 31 committees, each of which deals with a different subject area, and five committees that deal with procedural or administrative matters for the house. Most members serve on two or three different committees.

In the Senate, the presiding officer is the Lieutenant Governor, who is not actually a member of the Senate. The Lieutenant Governor is the second-highest-ranking officer of the executive branch of government and, like the Governor, is chosen for a four-year term by popular vote in a statewide election.

The first thing that the Speaker of the House and the Lieutenant Governor ask their respective chambers to do is to decide on the rules that the legislators will follow during the session. Some legislative procedures are provided for in the state constitution, but additional rules can be adopted by a house of the legislature if approved by a majority vote of its members.

Once rules have been adopted, the legislature begins to consider bills.

Introducing a Bill

A representative or senator gets an idea for a bill by listening to the people he or she represents and then working to solve their problem. A bill may also grow out of the recommendations of an interim committee study conducted when the legislature is not in session. The idea is researched to determine what state law needs to be changed or created to best solve that problem. A bill is then drafted by the legislator, often with the help of an interest group and with legal assistance from the Texas Legislative Council, a legislative agency that provides bill drafting services, research assistance, computer support, and other services for legislators.

Once a bill has been written, it is introduced by a member of the House or Senate in the member’s own chamber. Sometimes, similar bills about a particular issue are introduced in both chambers at the same time by a representative and senator working together. However, any bill increasing taxes or raising money for use by the state must start in the House of Representatives.

Representatives and senators can introduce bills on any subject during the first 60 calendar days of a regular session. After 60 days, the introduction of any bill other than a local bill or a bill related to an emergency declared by the governor requires the consent of at least four-fifths of the members present and voting in the house or four-fifths of the membership in the senate.

After a bill has been introduced, a short description of the bill, called a caption, is read aloud while the chamber is in session so that all of the members are aware of the bill and its subject. This is called the first reading, and it is the point in the process where the presiding officer assigns the bill to a committee. This assignment is announced on the chamber floor during the first reading of the bill.

The Committee Process

The chair of each committee decides when the committee will meet and which bills will be considered. The House rules permit a House committee or subcommittee to meet: (1) in a public hearing where testimony is heard and where official action may be taken on bills, resolutions, or other matters; (2) in a formal meeting where the members may discuss and take official action without hearing public testimony; or (3) in a work session for discussion of matters before the committee without taking formal action. In the Senate, testimony may be heard and official action may be taken at any meeting of a Senate committee or subcommittee. Public testimony is almost always solicited on bills, allowing citizens the opportunity to present arguments on different sides of an issue.

A House committee or subcommittee holding a public hearing during a legislative session must post notice of the hearing at least five calendar days before the hearing during a regular session and at least 24 hours in advance during a special session. For a formal meeting or a work session, written notice must be posted and sent to each member of the committee two hours in advance of the meeting or an announcement must be filed with the journal clerk and read while the House is in session. A Senate committee or subcommittee must post notice of a meeting at least 24 hours before the meeting.

After considering a bill, a committee may choose to take no action or may issue a report on the bill. The committee report, expressing the committee’s recommendations regarding action on a bill, includes a record of the committee’s vote on the report, the text of the bill as reported by the committee, a detailed bill analysis, and a fiscal note or other impact statement, as necessary. The report is then printed, and a copy is distributed to every member of the house or senate.

In the House, a copy of the committee report is sent to either the Committee on Calendars or the Committee on Local and Consent Calendars for placement on a calendar for consideration by the full house. In the Senate, local and noncontroversial bills are scheduled for senate consideration by the Senate Administration Committee. All other bills in the Senate are placed on the regular order of business for consideration by the full Senate in the order in which the bills were reported from the Senate committee.

At the beginning of each legislative session, a “blocker bill” is placed on the regular order of business. This bill will never be brought to the floor for action. Consequently, unless the sponsor of the bill has talked to the president of the Senate, indicating intent to suspend the rules and bring a bill to the floor, the bill will not be considered. Thus, the president of the Senate maintains a so-called “intent calendar,” which determines the order of business in the Senate. In 2021, the Senate Rules required a vote of 18 members to suspend the rules so that a bill on the intent calendar could be considered on the floor.

Floor Action Floor Debate

education reform bill on the House floor in 2019. Image Credit: Andrew Teas License: CC BY

When a bill comes up for consideration by the full House or Senate, it receives its second reading. The bill is read, again by caption only, and then debated by the full membership of the chamber. Any member may offer an amendment, but it must be approved by a majority of the members present and voting to be adopted. The members then vote on whether to pass the bill. The bill is then considered by the full body again on the third reading and final passage.

A bill may be amended again on the third reading, but amendments at this stage require a two-thirds majority for adoption. Although the Texas Constitution requires a bill to be read on three separate days in each chamber before it can become law, this constitutional requirement may be suspended by a four-fifths vote of the chamber in which the bill is pending. The Senate routinely suspends this provision in order to give a bill a third reading immediately after its adopted on second reading. The House rarely suspends this provision. However, since the readings are required on three separate legislative days, the House can recess at the end of one calendar day, reconvene the next calendar day, pass a bill on second reading, then adjourn. During the same calendar day, the House can convene a new legislative day, pass the bill on third reading, and the constitutional requirement is met even though the bill was read twice on the same calendar day. This is especially important at the end of the regular legislative session.

Voting on the Floor

In either chamber, a bill may be passed on a voice vote or a record vote. In the House, record votes are tallied by an electronic vote board controlled by buttons on each member’s desk. In the Senate, record votes are taken by calling the roll of the members.

If a bill receives a majority vote on third reading, it is considered passed. When a bill is passed in the house where it originated, the bill is engrossed, and a new copy of the bill which incorporates all corrections and amendments is prepared and sent to the opposite chamber for consideration. In the second house, the bill follows basically the same steps it followed in the first house. When the bill is passed in the opposite house, it is returned to the originating chamber with any amendments that have been adopted simply attached to the bill.

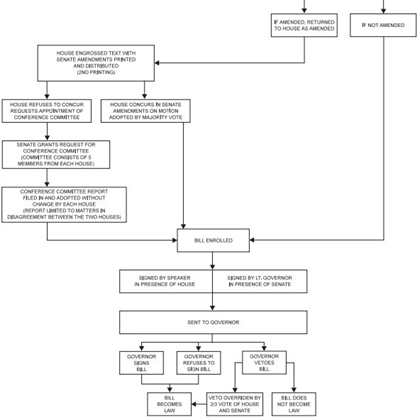

Action on the Other Chamber's Amendments and Conference Committees

The Texas Constitution requires a bill to pass both chambers in identical form. Consequently, if a bill is returned to the originating chamber with amendments, the originating chamber can either agree to the amendments or request a conference committee to work out differences between the House and Senate version. If the amendments are agreed to, the bill is put in final form, signed by the presiding officers, and sent to the governor.

Conference committees are composed of five members from each house appointed by the presiding officers. Once the conference committee reaches agreement, a conference committee report is prepared and must be approved by at least three of the five conferees from each house. Conference committee reports are voted on in each house and must be approved or rejected without amendment. If approved by both chambers, the bill is signed by the presiding officers and sent to the governor.

Governor’s Action

Upon receiving a bill, the governor has 10 days in which to sign the bill, veto it, or allow it to become law without a signature. If the governor vetoes the bill and the legislature is still in session, the bill is returned to the house in which it originated with an explanation of the governor’s objections. A two-thirds majority in each house is required to override the veto. If the governor neither vetoes nor signs the bill within 10 days, the bill becomes a law. If a bill is sent to the governor within 10 days of final adjournment, the governor has until 20 days after final adjournment to sign the bill, veto it, or allow it to become law without a signature. At this point, the governor’s veto is absolute since the legislature has adjourned, and only the governor can call the legislature back for a special session.

Enactment (When Laws Go Into Effect)

Any bill passed by the Legislature takes effect 90 days after its passage unless two-thirds of each house votes to give the bill either immediate effect or earlier effect. The Legislature may provide for an effective date that is after the 90th day. Under current legislative practice, most bills are given an effective date of September 1 in odd-numbered years (September 1 is the start of the state’s fiscal year).

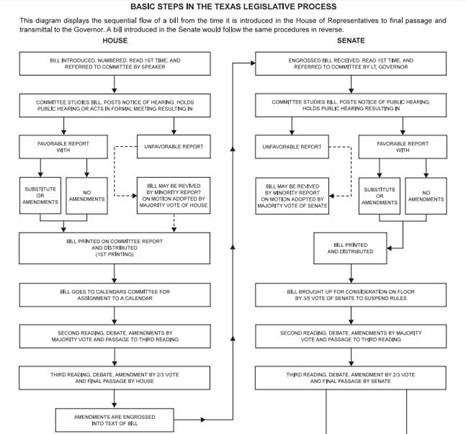

Basic Steps in the Texas Legislative Process (Diagram)

Constitutional Amendments

Proposed amendments to the Texas Constitution are in the form of joint resolutions instead of bills and require a vote of two-thirds of the entire membership in each house for adoption. Joint resolutions are not sent to the governor for approval, but are filed directly with the secretary of state. A joint resolution proposing an amendment to the Texas Constitution does not become effective until it is approved by a simple majority of Texas voters in a general election.

Link to Learning

Want to Get Involved?

Check out the Citizen Handbook the Secretary of the Senate, which includes information on the legislative process in Texas, advocacy etiquette, and guidelines.

The Texas Legislative Council has provided a detailed description of the legislative process in Texas.

You may research past and current legislation at the Texas Legislature Online.

Licensing and Attribution

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

Revision and Adaptation. Authored by: Kris S. Seago. License: CC BY: Attribution

PUBLIC DOMAIN CONTENT

How a Bill Becomes a Law. Authored by: Texas House of Representatives. Located at: https://house.texas.gov/about-us/bill/ License: Public Domain: No Known